If you’d told me five years ago that I would be flying to Chicago in March to attend a supply chain and logistics show, you would have been greeted by a momentary blank stare, followed by the image of a man attempting to determine in real time where his life went off-track. This is absolutely no criticism of supply chain and logistics shows generally — nor the people who attend them — but it’s a surprising destination, given where I envisioned my career heading.

Taking the elevator to the fourth-floor press center on Monday, I was struck by how (in a significantly more metaphorical sense) supply chain and logistics shows came to me. I’ve covered robotics off and on for around a decade now, but it was only in the past five or six years that it became a core component of my work. In that same time, the warehouse world has changed dramatically to the point where ProMat is more robotics than not.

The fourth floor of McCormick Place affords that kind of bird’s-eye view. The first thing you see looking out those windows is the giant Locus sign. Look beyond that in either direction, and you can spot virtually every one of the company’s competitors. This morning at my extremely unofficial office hours at a nearby cafe, a woman who works for U.K.-based Dexory described the inventory automation’s rough location on the show floor as being in the “robotics hall.” I countered that there’s no robotics hall if all the halls are robotics.

Locus Robotics Acquires Waypoint Robotics Image Credits: Locus Robotics

Walking down the physical margins of the show, you’ll see more traditional vendors. These are the people who make slip guards and plastic barriers. It’s easy enough to imagine five to ten years ago, when they set up shop closer to the show’s center, and those early robotics startups were the weirdos. Those more traditional products are, of course, still very much a necessary part of operating a warehouse or fulfillment center, but they’re suddenly out of the spotlight here, having been slowly pushed to the sides by tech companies flush with the VC cash necessary to build giant, garish two-story booths.

At a post-show happy hour last night, a VC asked me what the hardest part of learning the industry was. I told him that it wasn’t the robotics or AI. Sure, there’s a lot of extremely complex stuff happening under the hood that I — a creative writing major — will likely never fully grasp. But if you’re reasonably sharp, you can figure enough things out in broad strokes to carry on conversations and ask the right questions. The hardest part is learning everything that surrounds the robots. You have to learn the ins and outs of the industries these technologies effectively exist to serve, and the fact is that — in a reasonably short amount of time — it will include virtually ever industry out there. Logistics is, of course, the first step.

As you survey the show, things are thrown into a fascinating light when you recognize how much of the landscape was a direct result of Amazon’s 2012 acquisition of Kiva Systems. The first direct result was that seemingly overnight every retailer is thrust into the world of same- and next-day deliveries. For better or worse (mostly worse, if I’m being honest), that’s what customers expect now, and if you’re unable to deliver it, there’s a reasonably good chance they’ll leave for the one company that absolutely can.

The other piece of that puzzle is that when Amazon buys a company like Kiva, it drops all of its customers. Suddenly, all of the people who relied on that technology are left out in the cold. Locus CEO Rick Faulk and I discussed how the company was born as a direct result of the acquisition. The 3PL company Quiet Logistics was suddenly cut off from Kiva access, so it went ahead and built its own. Locus was spun out three years later. A day later, 6 River Systems (now owned by Shopify) co-founder and co-CEO Jerome Dubois told me that he had served as Kiva’s director of global sales and worked directly with Faulk. Small worlds within small worlds.

6 River Systems flagship robot, Chuck, helps warehouse workers pick items faster. Image Credits: 6 River Systems

Not every company’s origin story directly parallels either of these, of course. Some big players in the logistics space built their own robotics divisions in-house, while Zebra-owned Fetch is a descendant of Willow Garage. But how that South Bay startup’s collapse launched its own micro-industry is a story for another day, friends.

While it’s been more than a decade since Amazon bought Kiva, there’s still a sense walking around these halls that we’re very much at the beginning of something. You can’t help but shake the feeling that something bigger is happening here. Even fierce competitors express a kind of mutual admiration, all while giving you a knowing glance that, actually, they have the real technology in the pipeline that will truly disrupt the industry.

Walk around for a few more minutes, and you’ll notice something also. Something like 80% to 90% (completely pulling this number out of my butt here) of the robots fit into one of two categories. First are those Kiva-style mobile robots (the big Roomba, if you will). There are differentiators, of course, but broadly, these are robots that drive around a warehouse floor — either autonomously or following around a human — carrying goods. That could be boxes, or it could be tools — whatever relatively small thing it is. They’re often, but not entirely, a departure from the Amazon systems, which are designed to move shelving units around.

Image Credits: Getty Images / Teera Konakan

The other big robot archetype is one we all know and love: the robotic manipulator. The classics are classics for a reason. Here these things are generally used to pick up and place items in boxes. The exhibitors were a mix of arm manufacturers (Kuka, Fanuc, Yaskawa) and startups that utilize those arms (including Covariant, Ambi — competitors birthed out of neighboring UC Berkeley Labs).

Generative AI was somewhat top of mind (SVB, too, but for dramatically different reasons, of course). Hyped, yes, but I’m comforted by the fact that this space wasn’t all-in on the whole blockchain/crypto thing a few months back. Adopting new technologies is largely pragmatic here. Some see the category informing their work. Learnings from the space could prove useful in teaching robotics or in fleet management, for example. The responses to my questions were predictably measured in this room full of deeply practical people.

There are two key reasons companies buy robots beyond the above Amazon conversation. The first is smaller and more cynical: it’s good PR. This usually manifests itself in front of house deployments. A robot barista, for example, isn’t especially useful right now, but it certainly looks neat. Consumers are attracted to neat. I might shoot some vertical video for TechCrunch’s TikTok account, but I’m not going to write some 1,000-word article drilling down on its machinations, while telling that you’re looking at the future.

It’s also, frankly, important to show shareholders that yours is a forward-thinking business that is continually evolving to adapt to these ever-changing times. That’s where pilots come in, which is, in turn, why at lot of announcements you see around early trials ultimately don’t bear fruit.

The second is purely economic. It’s obvious on the face of it, but companies buy products that save time and money. If the technologies fail to do so, they will likely be abandoned. I won’t bore you with my spiel about the potential for human collateral — I’ve had my fill of, let’s say, spirited discussions on the subject this week, and I will likely remain skeptical, because someone has to. But the question of how many humans and robots to staff a warehouse with is governed by the bottom line. The novelty of these robots wears off extremely fast. If they’re not living up to their promise, it’s time for a new approach.

While there are some technologies here that can outperform human labor, I’ve found that, by and large, human speed is currently the gold stand. Take palletizing. It’s an impressive and complex feat with a lot of variables (though truck loading has an added layer of complexity and is therefore still aspirational for many solutions), and doing it at the same speed as a person is the current target for many. But charging units excepted, robots don’t take breaks and can work through the night as needed – and are therefore an appealing option for many companies.

As I see it, there are presently two magic bullets for the industry. The first exists in that liminal space between the aforementioned robotic form factors. If I were a VC in the robotics space right now, in addition to making a lot more money, I would be hyperfocused on precisely this. Whoever develops a truly mobile robot capable of maneuvering down factory aisles (i.e., around the size of a 6 River/Locus/Fetch robot) mounted with a mobile manipulator capable of picking things off the shelf at a decent clip and a variety of speeds should clear out room in their driveway for the Brinks truck delivery.

It’s hard to overstate how much this will crack things wide open, and many of the aforementioned companies are less interested in going back to the drawing board than addressing the current massive market of factories looking to take the first steps toward automation.

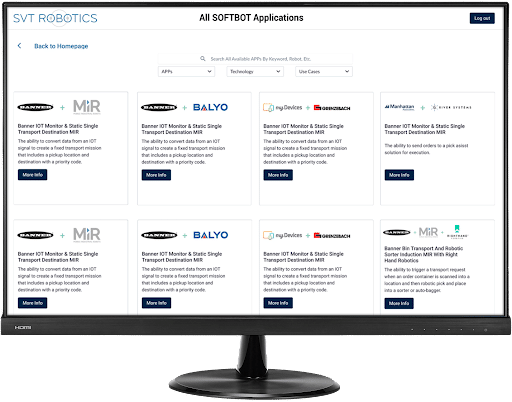

Image Credits: SVT Robotics

That brings me to magic bullet two: interoperability. An important thing to remember: While we’re not quite at the point of lights-out fulfillment centers (manufacturing is a different story), getting close requires a lot of different solutions from a lot of different companies. There’s a reason Amazon has made a bunch of subsequent acquisitions — these are, for the most part, single-purpose systems. Beyond this, a lot of larger companies have opted to diversify so as to not get left in a lurch similar to what Staples, Gap and Office Depot experienced post-acquisition.

Putting all your eggs in a single basket leaves you in an extremely uncomfortable position when the competition buys and discontinues support for the technology into which you’ve poured countless time and money. The broader question here is how a warehouse operator gets all of these heterogenous systems to play nicely with each other. That requires fleet management, data exchange and complementary components among others.

Everyone’s got their own systems with their own technologies and APIs, and so far there’s no approach here akin to the Matter Alliance that was co-created by all of the biggest names in the smart home space. (I write about a lot of consumer electronics. These are analogies my brain can make sense of). A lot of companies have built their own in-house fleet management software, with varying degrees of interoperability (very much trending to the low end). A number of solutions are currently looking to be that truly hardware-agnostic platform for deployment and control. I had a nice chat this afternoon with SVT Robotics out of Virginia, which is one of the more compelling operators in the space and has partnerships with all of the big hardware players.

MassRobotics’ push to create interoperability standards is absolutely in the conversation as well. Founded in 2020, the org describes its plan thusly,

The group’s mission is to develop standards that will allow organizations to deploy autonomous mobile robots AMRs from multiple vendors and have them work together in the same environment, better realizing the promise of warehouse and factory automation. These standards will allow autonomous vehicles of different types to share information about their location, speed, direction, health, tasking/availability, and other performance characteristics with similar vehicles so they can better coexist on a warehouse or factory floor.

Image Credits: Pickle Robot

As to more immediate issues, truck unloading (and eventual truck loading) was a big deal this year. This is among the crappiest warehouse jobs you can assign to a human. In addition to being incredibly rough on the body, the shipping containers mostly sit outside of a warehouse, exposing them to the elements, which makes them unbearably hot or cold. “We thought that was the hardest problem, and it hadn’t been solved yet,” Pickle CEO Andrew Meyer told me.

There’s a reason Boston Dynamics’ first purpose-built commercially available robot is focused on this category. The company’s head of warehouse, Kevin Blankespoor, told me how their own Stretch could be the first step to a bigger world, including magic bullet number one mentioned above. “I think there are versions of something that looks like Stretch, or even a combination of Stretch and Atlas,” he said, “where it’s a smaller footprint that works in a tighter space. We’re excited about all of these things.”

It’s also, frankly, not difficult to imagine breakthroughs made here that inform future robots in different categories, much like the way autonomous driving gave a huge boost to warehouse robotics. Systems designed for agriculture, construction and the home will almost certainly take cues from what continues to be the hottest robotics category.

Image Credits: Agility Robotics

Certainly Agility’s Digit feels like a peek at a broader world. Warehouse is really the tip of the spear as far as applications for legged robots — it’s simply the task that makes the most sense right now from the standpoint of market need. General-purpose humanoid robots continue to be a hot topic now, but efficacy is a huge question mark. I believe that also applies to drone inventory systems like Corvus, Gather AI and Verity, which were all clustered in the back of the hall, in a sport reserved for smaller startups. I love the idea of finding more practical uses for drones, and hope someone cracks this.

Walk around the floor long enough, and you’ll overhear dozens of conversations about RaaS (robotics as a service). All the cool kids are monetizing with it. Certainly some manner of subscription model makes sense in most instances. These systems cost a lot up front — money many in the mid-market and below don’t have on-hand. A monthly fee also affords opportunities to issue software improvements and support.

Another happy side effect of the model is a sustainability angle. As Faulk pointed out, the raas approach affords Locus the ability to keep devices in circulation. If something stops working, you ship it back, they fix it out and send it back out to you or someone else. Ditto if the customer is simply done with the service — do some repairs, rebadge it and send it to a new client.

Faulk told me that of all the Locus units deployed in the world, only a handful or two (unclear if it’s a metric or imperial handful) have been scrapped. As for what took those robots out of circulation? He had a simple response: forklifts. Crushing the robot from above with a couple of big metal prongs is apparently the one surefire way to take a LocusBot out of circulation — information you’ll hopefully never need to put into practice.

That’s precisely the model companies want when dealing with unproven startups. You certainly don’t want to be in a position of spending a bunch of money upfront on a product that folds the next day. Bigger companies with established partners, on the other hand, may find more value in just buying a solution out right. The consensus answer here is to figure out want clients want and work it out for them. Offer both solutions and, perhaps, a hybrid. Don’t add obstacles where the aren’t necessary.

It’s been a productive few days for me, and I may end up becoming a regular on the supply chain and logistics circuit as a result. There’s so much I just managed to scratch the surface of. I had some productive chats about things like packing tracking software I’m looking forward to digging into (cue the press releases). Vision systems are extremely impressive and only getting better. Fun nugget from speaking with startups like SLAMCore and Covariant: Lidar is really out of vogue here. Stereoscopic cameras already do something better (e.g., reflective surfaces) and are catching up on the rest. That’s why there are Intel RealSense and competitors in most of the new robots you’ll see.

I’ve got to hop. There’s one more VC happy hour I need to get to. If you told me five years ago that I would be saying that, I would have probably smugly replied, “Yeah, obviously.” I’m working on that part of my personality. Listen, it’s a process. I’m going to leave you with a chunk of my conversation with Boston Dynamics’ Kevin Blankespoor because I think it’s super interesting and hopefully you will, too. Lots more to start transcribing on the way home. See you next year in Atlanta, probably.

Meantime, I still have a handful of interviews from the event I need to post, so look for those on the site and in next week’s newsletter.

Q&A with Boston Dynamics’ Kevin Blankespoor

Image Credits: Boston Dynamics

TC: Boston Dynamics didn’t have a focus on commercializing for a long time. It really happened under SoftBank.

KB: Google a little bit, but SoftBank was the big push, for sure.

Atlas’ ability to move around boxes was more of an edge case. There was interest from potential clients, but there was never a plan to commercialize.

Yeah. [Atlas] is a general-purpose robot, so if you want to go explore an application, it can do the vast majority of them, just like a person can. It may not be the right optimization when you’re said and done, but it’s how you understand the application and you can peel off and do a derivation of Atlas, basically, and go make that into a product. With Atlas and case handling, we found that to be an attractive match, and I peeled off a big part of the Atlas team to do Handle, the two-wheeled robot. That was a foray into combining wheels and legs, which we always wanted to do, but also it was a little more simple and could handle cases in a warehouse.

We actually did a few experiments with customers there and then we went to Stretch. But it all really started with Atlas. A lot of the hardware tidbits from Atlas and Spot are on Stretch. It’s totally different, but under the hood, there are similarities.

What’s an example?

If you look at the hip actuators on Spot, they’re basically the same as the wrist actuators on Stretch, but Stretch is a lot bigger. The vision system across Atlas, Stretch and Spot all use a lot of shared software. We really don’t have to start from scratch when we bite off a new product. We have a big war chest of technological building blocks.

Was Kinema a part of that?

On the box detection side, absolutely. Kinema has the best box detection machine learning pipeline out there. We’ve expanded it a lot on Stretch, but that’s absolutely what it’s running now.

Discussing truck unloading has been eye-opening. Not only is it extremely physically taxing on workers, but those trailers are also exposed to the outdoors, making it extremely hot or cold inside.

It can be dangerously hot. Sometimes I’m shocked to see that they let people go in when it’s 110 degrees in there. And it gets super cold in the winter.

Is hot or cold harder?

Cold is generally a challenge. We did bigger temperature extremes in our DARPA days. When you go out in the snow, and nobody’s laptop will boot up, but your robot still does. But once you’re up and running, robots generate their own heat. That’s why there’s cooling vents all over it. The computers heat up, the actuators heat up. That works against you in hot environments.

Everyone is talking about humanoids right now. After so many years and so much money in R&D, you had a lot of potential customers expressing interest. Did you explore the humanoid form factor for what ultimately became Stretch?

We didn’t explore the route because we thought it would be somewhat more expensive and complex than it needs to be. Keep in mind, that was about seven years ago. It’s amazing that we’re able to sit here and talk about maybe four or five different companies that are going after real products with humanoid robots. That’s fantastic.

Even Agility has something humanlike.

They’re definitely in that conversation. I’m just excited that if you had asked me that five or 10 years ago, I’d so, “Oh, that’s way too expensive. That’s way too complicated.” And now you’re finding multiple companies are looking at this and saying, “We think there can be a real business here.”

But for you, the move was focusing on the best robot for a single, specific task. That’s how we ended up with Stretch. It is a multipurpose robot in that the hardware is capable of doing lots of different jobs in warehouses. We’re starting off unloading trucks as our first application. That’s our first focus, but we are also in time going to be able to do things like build pallets and load trucks. In the future, a day in the life of Stretch might be spending the morning on the in-bound side and unloading boxes from containers. And spend the afternoon in the warehouse building pallets and it might move in the evenings to the outbound side loading boxes back into trucks. It really is going to be a single robot that you can do for multiple jobs.

It sounds like that’s far off.

We’re rolling out new applications every couple of years. We’re focused on getting it out of the gate.

Why didn’t Handle work out? The counterweight system was very cool, but was it ultimately more robot than was needed for the situation?

We actually found that Handle wasn’t fast enough. We took Handle out for a couple of different trial runs in warehouses. The first application was pallet loading, which looked pretty good. The second was truck unloading. What we found with Handle in the back of a truck is it had to do a fair amount of maneuvering in the space to move a single box […] It would take about 25 seconds per box. People can move a box in maybe five seconds. We knew we needed to hit that kind of number for a return on investment. Stretch can do that. It uses the arm more completely and only moves the base when it needs to.

We were talking about Stretch moving from Point A to Point B in a warehouse. But when it’s working on a shelving system, it’s able to move along the shelves [for picking]?

Correct.

Interoperability is the big topic of conversation this week. What is Boston Dynamics’ approach to this? If you want close to a fully autonomous robot at this point, you’re going to have to work with a lot of different robots from a lot of different companies.

Absolutely. It’s a hot topic. Both heterogenous fleet management. We’re seeing a lot of different companies take that on. We have prototyped our own fleet manager to understand what the hard parts are. Spot has Scout, which is its own web client for teleoperation, industrial inspection and autonomy. So we have a version of a fleet manager now. I think we have yet to see how that’s going to shake out.

Developing your own fleet manager is a resource-intensive way to understand the problem.

Yeah. I mean, part of it was that, to do the things we wanted to do, there wasn’t a fleet manager you could buy. One of the things we want to do as a future application is case pick. That’s where the robot is in the aisle and it’s building up pallets of different boxes. It’s a really big application. We’ve played with different ways to do that. One is with autonomous forklifts. It moves the pallet through the facility back and forth down the aisles and Stretch rendezvous at each point location and the pallet wrap. We’ve prototyped that. We’ve done it with a couple of different partners. We’ve done it with Stretch on its own, where it’s dragging its own pallet, just to get a feel for where the hard parts are.

But you’ve decided not to go further with that?

No, we will. We basically decided to focus on application number one right now. We want to get it to the performance, reliability and robustness that customers are happy with. That’s all hands on deck. But we’ve still got a lot of the software and knowledge from when we did the picking thing I described, and that will pick up in the not too distant future.

So we can expect to see fleet management software from Boston Dynamics?

Maybe. To be determined. We’ll definitely have that for our robots. Will we have a heterogeneous manager that will work with other robots? I don’t know.

You survey the landscape, and if someone is already doing it well, you focus your attention elsewhere.

Exactly. We don’t want to do that as a primary business. If we can buy something that really works, that would be really interesting.

You mentioned the mobile picking robot. I think that’s a magic bullet. If you’ve cracked that, you’ve cracked warehouses.

Yeah. And even more generally, the thing I’m excited about is mobile manipulation. If you move around these types of shows, you’ll see a lot of mobility. There are a lot of autonomous mobile robots and forklifts. You’ll see a lot of people doing just manipulation — everything from cobots to industrial arms. But there really is nothing out there at scale that does mobility and manipulation together.

I spoke with the CEOs of Locus and 6 River Systems. They’re really just operating in that mobility segment and having a lot of success. But successfully mounting an arm to one of those robots in a way that works is going to be huge for this industry.

I don’t know that they have the motivation to tackle something even more complicated. They have so much market penetration to go with the existing product. But for us, it’s core to what we do. Stretch is a mobile manipulation robot. It’s in the warehouse now. I think we’re going to grow in the warehouse for a long time. It’s going to go beyond the warehouse in time. Spot with an arm is a very capable mobile manipulation robot. Atlas as well, we’re starting to get more into manipulation. For Boston Dynamics, that really is the evolution, to go into mobile manipulation.

What is the upper weight threshold for Stretch’s picks?

Fifty pounds.

What are the constraints, in terms of weight?

A couple. Grasping is one. Suction is amazing. People are always amazed by how much it can pick up. But, when you start getting into imperfections like a damaged box — those top boxes, you can’t fit the gripper above it. You have to get the front face. That’s where some of the limitations come in.

If we’re talking about a mobile system that can pick, in order to compete with companies like Zebra, Locus and 6 River Systems, you’re going to have to scale down. Does that make sense for Stretch?

Yeah, absolutely. I think there are versions of something that looks like Stretch, or even a combination of Stretch and Atlas, where it’s a smaller footprint that works in a tighter space. We’re excited about all of these things.

Repeatability has to be one of the biggest issues entering the commercial space.

Yeah. Making a cool demo video is great, and I love it. I’ve done a lot of them. The difference between that and a product that works for a customer all day, every day, has sufficient hardware reliability and software robustness so it can handle all of the surprises you get — that’s an order of magnitude more work. That’s what we’ve done with Stretch. Stretch is never going to be a highlight reel, but Stretch works.

Conventional wisdom by Brian Heater originally published on TechCrunch

from TechCrunch

via Click me for Details

No comments:

Post a Comment